Smart Mobility, opportunities and threats

Gerard Tertoolen

(Paper presented at the Digital Freedom Festival in Riga (Latvia), 29th of november 2018)

In terms of mobility, the Netherlands is an interesting country, because it is small, yet densely populated. The Netherlands has a land area of 42,500 km2 and a population of over 17 million. Latvia, for instance, is considerably bigger, at 64,000 km2, but has a population of under 2 million.

When combined with our high level of prosperity, our ever-growing population causes major traffic jams in the morning and evening rush hours. In 2018, traffic jam severity (the length of all traffic jams multiplied by their duration) is already 20% higher than last year. Considerable efforts are made to curb traffic jams, but no true solution has been found as of yet. Widening and building new roads only has the effect of drawing more traffic and any attempts to change driving behaviour and to tempt car drivers to use the train or bike or work from home simply are not effective enough. For many, the car is still mode of transport number one.

Now though, there is a new weapon in the fight against congestion: Smart Mobility. If people can’t solve the problem, it’s up to technology. Let us now take a somewhat closer look at Smart Mobility.

Introduction of Smart Mobility

First of all, ‘Smart Mobility’ is a fine example of framing. Framing is a technique that involves explicitly using words that the intended audience will be susceptible to. Nobody wants to be stupid and everyone considers themselves to be smart, so any type of mobility that’s smart must also be good. In this paper, I will present a number of leading examples of Smart Mobility in the Netherlands and examine what they will mean for travellers from a psychological perspective.

I’ll now briefly mention three (leading) Smart Mobility projects in the Netherlands.

- Project Socrates 2.0

The underlying idea behind this project is that road users are currently offered sub-optimal traffic information, which is why Socrates 2.0 aims to provide users with better travel advice. Within Socrates, new services are being developed in the field of smart routing, real-time speed and lane advice, local information about (temporary) road closures, accidents and improved road traffic management measures.

- Project Talking Traffic

Various private and government parties cooperate in this project, which is centred around connectivity, data availability and the introduction of intelligent traffic control systems (traffic lights). If vehicles are able to communicate with each other and with equipment installed along the road, traffic flow can be improved. Talking Traffic provides next-generation travel information and connectivity that gives you access to good information before you leave and lets you look ahead beyond your windshield during your journey.

- Project Concorda

Various parties around Amsterdam are working together in a sub-section of a major European project involving autonomous cars. The objective is to test autonomous cars on motorways and the associated infrastructure. Autonomous cars are capable of driving very closely together without causing accidents, which will drastically increase the capacity of our road network.

These all seem like great projects and tremendous developments. Soon, we won’t have to drive ourselves but be chauffeured around instead. Besides, all vehicles will be connected and we’ll know everything we need to know in advance, so that nothing in traffic will surprise us. Accidents, traffic jams and annoyances will be a thing of the past. It sounds like a fairy tale. The question, then, is whether our mobile future is actually that rosy. There are a lot of threats lurking that are not so much technical in nature, but rather human. Now, let’s have a look in the human brain, before we return to technology.

Our stubborn brain

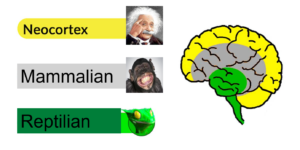

Roughly speaking, our brains are made up of three distinct parts.

- The reptilian brain

The oldest part of the brain, in evolutionary terms, is what we call the reptilian brain. When we sense (potential) danger, it is activated immediately. This part of our brain is capable of three primitive responses to threating stimuli from our environment: fight, flight or freeze. If we are to really accept Smart Mobility as the future of transportation, we will have to make significant changes to a number of aspects of our behaviour, which is exactly when our reptilian brain will pump the brakes. I’ll now go over four obstacles in the way of change that originate in our more primitive brain:

- self-overestimation. On average, we estimate that our own skills are slightly superior to those of others. Research has demonstrated, for instance, that much more than 50% of people believe that they’re better-than-average drivers. This is as impossible in statistical terms as it is interesting in psychological ones. If we think that we’re better than others, we also think we don’t need to change our behaviour. We’ll leave that to the less gifted among us.

- Loss aversion. Research conducted by behavioural economist Richard Thaler has shown that loss has twice the impact on our emotions compared to winning. Our aversion to loss has been shaped by evolution. People who used to actively avoid losing their food or health, for example, were more likely to survive. By now, avoiding loss has become automatic for us. Change comes with the risk of losing the control that our automatisms have convinced us we have, so we instinctively prefer that all things stay the same.

- Attribution bias. We are more likely to attribute things that go well to ourselves (internal attribution) and will typically point to others when things go awry. And if we’re not the cause, why should we change?

- Epinosic gain or victimisation If you’re ill, you need a doctor. By victimising yourself, you release yourself from the obligation to act: “It’s up to the government to solve traffic jams; I can’t do anything about it.”

- The mammalian brain

We’ll now switch to a more complicated part of our brains, the so-called mammalian brain, which is also known as the limbic system. As opposed to the reptilian brain, this part of the brain can recognise emotions, and our behaviour is partly determined by our mood. This part of the brain is susceptible to conditioning (we repeat behaviour that results in a reward and avoid behaviour that leads to punishment). In addition, we also align our behaviour with that of other people (imitation and social comparison).

- The neocortex

The ‘neocortex’, the outer shell, is where you’ll find our human brain. It lets us link cause to effect, look forwards and backwards in time and make well-considered choices. It’s the birthplace of fantastic discoveries and innovations, just like Smart Mobility. This does not mean, however, that this part is lord and master. The more primitive parts of our brain regularly rise up in revolt and can even take over complete control on occasion.

A quick example. Cars are a convenient way to travel from A to B. When we think about cars in this way, we can hear our neocortex talking: they’re quick, efficient and useful. That’s not all that cars are, however. They also give us status, for instance, the opportunity to challenge others on the motorway and even evoke territorial behaviour. These responses are governed by the mammalian brain. We can descend even further, though: cars give us anonymity, power, opportunities for identification and compensation. We have now penetrated deep into the reptilian brain, where we can see that cars are, in fact, a delightful mental cocktail. A volatile mixture for some, but most of us see it as an enjoyable emotional blend that can occasionally provide relaxation and a way to unwind. In autonomous cars, though, we will no longer be drivers, but passengers. The technology produced by man will begin to threaten man, or keep him from some of his joys in life, at least. In the end, philosopher Martin Heidegger will be proven right: ‘More machines means fewer humans!’

Focus points when developing Smart Mobility

The development of Smart Mobility in the Netherlands is primarily ‘technology driven’, and too little attention is paid to the human factor. Let’s look at a few blind spots in the development of Smart Mobility:

- Smart Mobility leads to dumb drivers

Just like our bodies, our brains benefit from training and exercise. Laziness, however, is lurking. When the calculator was invented, we all stopped performing mental calculations. Ultimately, this has meant that we have also started losing the ability to judge whether the answers given by a calculator are right in the first place. Recent research has shown that navigation systems have a similar effect. If you trust your navigation blindly, you stop using some parts of the brain. The hippocampus (the ‘seahorse’) is a group of brain cells present in both hemispheres of the brain that play an important role in searching for and determining our position in space. Psychologists working at University College London (UCL) found that the hippocampus is deactivated when we use navigation systems in our car. It has also been shown that people who rely almost exclusively on navigation systems perform significantly worse when they can’t use technology than those who regularly try to find their own way around. Taxi drivers who had to learn the map of London by heart, research has shown, have a larger hippocampus than a group of control subjects. Moreover, the difference in size increases proportionally to the number of years of driving experience. It also works the other way around: doing it yourself is the best type of mental gymnastics. As more and more technology is being incorporated into cars (‘park assist, ‘automatic Hill-Hold control, ‘adaptive cruise control’), we’ll start to lose many skills.

- Trusting the cat to guard the cream

In the Netherlands a fierce war is being waged against distraction in traffic, with smartphones being one of the major culprits. Every year, dozens of people die as a result of smartphone use in traffic. At the same time, however, many information services are provided to car drivers through smartphones! A strange paradox indeed. Equally, as cars are made ever smarter, manufacturers are effectively spreading the message that drivers do not have to pay as much attention anymore. If cars can drive and brake by themselves, drivers are free to focus on other things, even though the underlying technology isn’t that advanced (yet). Combine these factors and you’ll have all the ingredients for life-threatening situations.

- Cars are emotion

All too often, cars are taken to be a mode of transport that brings people from one place to another. As mentioned before, cars are a lot more than that (freedom, status, emotion, etc.). When drivers become passive passengers rather than being in charge, the charm of driving will disappear. You can be sure that car enthusiasts – of which there are myriad – will not accept that lying down.

- Emptying the ocean with a thimble

Measures intended to increase the capacity of road networks (such as Smart Mobility) only provide temporary relief, as populations and the desire for mobility continue to grow unchecked. When more capacity is made available, it will attract more cars. In addition to the growth in the autonomous sector, there is considerable latent demand. People who have been forced into trains by all-too-frequent traffic jams will return to the motorway when they are given the space to do so. In the long run, the roads will clog up again, which is exactly what we see when roads are widened with extra lanes.

Five tips for Smart Mobility

As you may have noticed, I examine everything that’s happening in the world of Smart Mobility with a critical eye. Nevertheless, I cannot and do not want to stop progress. I’ll therefore conclude this article with a number of tips that will hopefully let Smart Mobility developments run more smoothly, whilst allowing us to reap the benefits of all that technology has to offer us.

- Involve Human Factors

Human behaviour, in particular those aspects mentioned above, should start to determine the course of future development, rather than technology alone.

- Focus on proponents and opponents

Smart Mobility in the Netherlands is currently a game that is mainly being played by believers. Techies and policymakers who are fully convinced by its merits determine the course, which means there is hardly any room for opposing voices to be heard. My advice: don’t just focus on the ‘believers’, but also listen to people with a more critical attitude. What are they troubled by and how can this be solved?

- Following is the new leading

Partly thanks to the influence of social media, contemporary consumer behaviour can be compared to flocks of birds: certain topics can be completely dominant one moment, before the mood shifts and the flock suddenly heads in a different direction. As in flocks of birds, there is no single boss: everyone has a part to play. If you only focus on your own topic (technology), you’ll end up losing sight of the flock. Instead, make sure that innovations can fit in with various topics and interests. For Smart Mobility, the same applies: the trick is to follow, rather than to try to lead.

- Don’t bite off more than you can chew

If we face steps or processes that are simply too challenging, many of us will lose interest. If your plate is too full, you’ll lose your appetite. Working in smaller steps and involving and rewarding people who help you take these steps, will accelerate progress. Don’t focus on the goal, but on the direction of the movement.

- Use our instincts

A large group of car drivers are currently averse to change. Rather than fighting them, you can tap into subconscious motivators, such as competitiveness (challenges, games), herd instinct (we are naturally inclined to follow others), our instinctive desire for power (we want to lead the way and be involved). Give people back control over their behaviour, in one way or another. Don’t let technology replace drivers, but let the two cooperate permanently.

Finally a warning

As our technological capabilities expand, humanity finds ourselves confronting one of the most important questions of our time: how will digital technology transform our society? Rapid and relentless innovation in a range of technologies—from artificial intelligence to virtual reality—will increasingly control us if left unchecked, setting the limits of our liberty and defining what is forbidden. Certain technologies and platforms, and those who control them, come to hold great power over us.  Some will gather data about our lives, causing us to avoid conduct perceived as shameful, sinful, or wrong. Others will force us to behave certain ways, like self-driving cars that refuse to drive over the speed limit. Those who control these technologies – usually big tech firms and the state – will increasingly control us.

Some will gather data about our lives, causing us to avoid conduct perceived as shameful, sinful, or wrong. Others will force us to behave certain ways, like self-driving cars that refuse to drive over the speed limit. Those who control these technologies – usually big tech firms and the state – will increasingly control us.

As time go on, we need more ‘philosophical engineers.’ And it will even become more important for the rest of us to engage critically with the work of tech firms. Put people at the heart of Smart Mobility. After all, the key to the door to change is always on the inside.

References

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Milieu, 2016, Smart Mobility, Bouwen aan een nieuw tijdperk op onze wegen, Den Haag.

- Susskind, J., 2018, Future Politics, Oxford University Press, Oxford,

- Voorzitter van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, 2018, Smart mobility Dutch reality, kamerbrief, Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat, Den Haag